In many of the conversations I have had around data science applications, the focus has often been around modelling, ML algorithms and hyperparameter tuning and deployment into production. Stakeholders often want to know the results - what it means for them or the business overall.

But one of the earliest steps in every data science project - that of exploratory data analysis - is severely underrated. This step is often dismissed as simply generating graphs and fancy looking charts, with none of the “meaty” stuff like model training, evaluation or deployment. Even I sometimes feel a bit conscious explaining that this is one aspect of my work in the overall scope of my data science projects.

But the more projects I work on, and as I speak to more data scientists, I find the need to emphasise the importance of this step.

1. It is a crucial step in understanding the data

I previously wrote about why it is important to “spend time with data”, before going into subsequent stages of the data science workflow. Taking time to understand the data - how it was extracted, the structure and schema, and what all the features stand for - can save a lot of headache further down the line.

EDA becomes an important part of this step. It allows us to understand what features are available, what their distributions are like, how they interact with each other and which features are most influential in any specific target variable you want to predict later on.

2. It can help uncover hidden data issues early

Sometimes, entire projects are based on flawed data, say mismatched join keys, duplicated time series, inconsistent labels. Think of EDA as your first checkpoint for quality control, before you do any heavy analysis or modelling. Let’s say you are building a sales forecasting model for a retail chain using transactional data. And during EDA, you notice that some stores show negative sales for certain days. This lets you inspect further and maybe you realise that these negative values are due to refunds being logged as negative revenue.

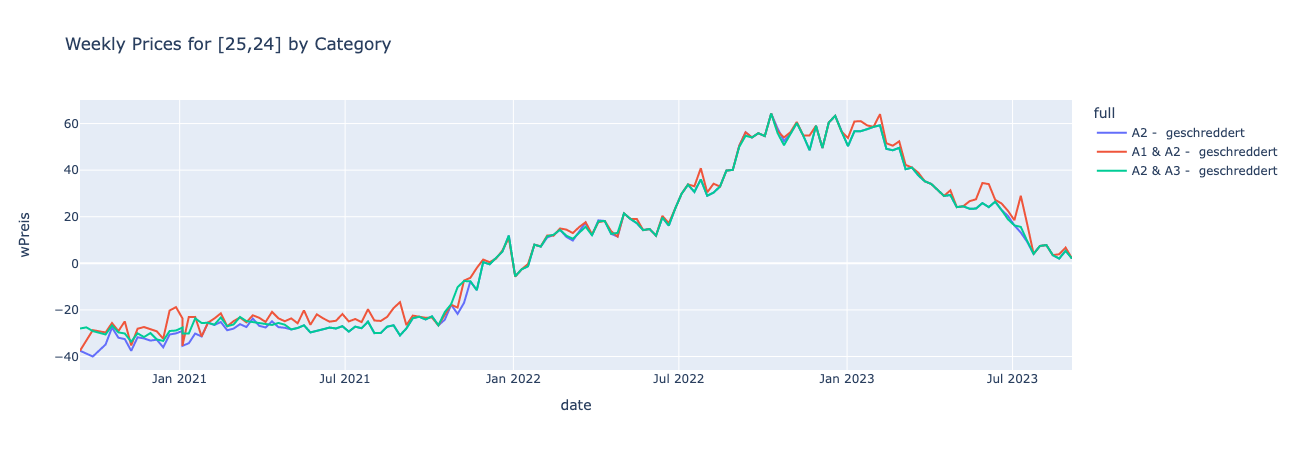

Something like this actually happened in one of the projects I worked on with a market-leading energy trading firm in Germany. The task involved finding factors determining the price of wood waste, as the firm’s business involved collecting this waste from sellers and selling it to power plants for energy generation. The data set contained historical values of the price of waste as recorded by the firm, for 3 years.

The price values were sometimes negative - these were instances where the firm got paid for collecting the waste from sellers. And when the price values were positive, it was a case of the firm paying money to collect the waste.

3. EDA helps define your modelling strategy

The insights from EDA often shape your model choice. It helps you figure out the distributions, patterns and relationships in your data, so that you can make more informed decisions about preprocessing steps, feature selection, and model choice. For example, it sheds light on questions like: Are the features linear? Is the target variable balanced? Is it a regression or classification task? The EDA step directs the decision on whether to use a linear model, tree-based method, or even rethink the problem.

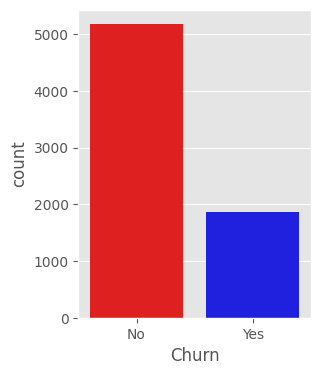

Again, something I encountered in my work. While working on a churn prediction model for a telecommunication firm, the EDA step revealed that the target variable was heavily imbalanced.

Churn:

No: 5174

Yes: 1869

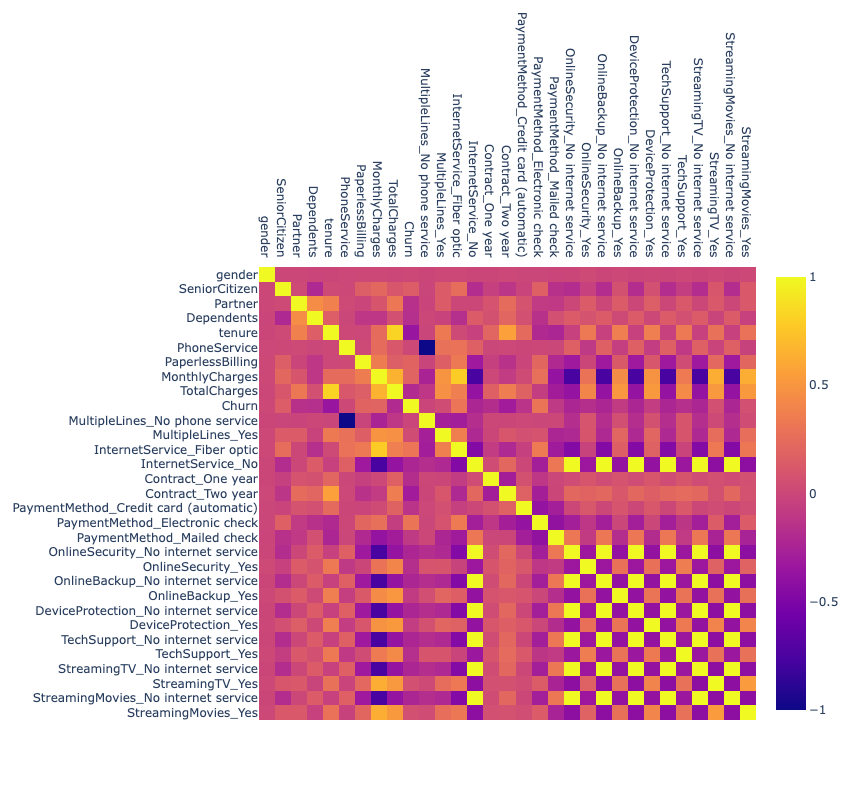

Almost 73% in favour of one label. This meant that I had to either use SMOTE or class-weighting for handling the imbalance. I also saw that some of the one-hot encoded categorical variables were 100% correlated (redundant) with each other (e.g. InternetService_No and OnlineBackup_No internet service etc.).

This would have led to multicollinearity and one of these pairs of 100% correlated features had to be dropped before modeling.

EDA also informed the choice of the model as tree-based models like CatBoost are better at handling non-linearity and categorical variables better than logistic regression.

4. You often have to return to EDA multiple times

I have often found that conducting EDA is not a one-off task. It is something we have to return to often at a later stage. For example, after modelling, we may find that the error metrics (RMSE, MAE or others) look subpar (or in the other direction - too good to be true). We test out different combinations of features to see how the RMSE changes.

This is when we go back to EDA and perhaps plot a correlation matrix of all the features, to find that there are features that are poorly correlated with the target variable, which can be dropped. Or that there are pairs of features that are highly correlated, which leads to multicollinearity - a feature that is undesirable for some ML modelling algorithms.

As such, the data science process is not a linear one but rather circular and we have to go back to EDA several times to redo the analysis.

5. You may have to redo EDA based on feedback

You may also have to go back to the start and redo the analysis again based on specific feedback you get from stakeholders. This could be due to a gap in understanding context, additional input from stakeholders who are closer to ground truth or changing business priorities.

As a simple example, you may find that the business has decided to change their pricing. This means that the features you considered previously for a clustering or MMM optimisation model may not be correct anymore. Or it could be cases where an entire product category has been paused, leading to new null values in your data.

6. It can be key for stakeholder communication

I have often found that the insights and visual summaries from the EDA stage can be used to communicate key insights for non-technical stakeholders. Stakeholders don’t always care about F1 scores or neural nets.

In presentations to non-technical stakeholders, I have found myself questioning the point of discussing ROC AUC scores and having to go in loops trying to explain confusion matrix and SHAP summary plots. Business teams really care about only how the data supports their decisions, and a lot of technical jargon can be avoided if we reuse the results from the EDA.

For example, if you are helping a marketing team understand campaign effectiveness across regions, you may only need to show:

- simple box plots of campaign ROI by region and find that one region consistently underperforms.

- a heatmap of feature correlations shows that age and campaign response are positively correlated — but only in certain income brackets.

- a simple bar chart showing that a large segment of customers receiving ads had already unsubscribed, indicating poor targeting.

And you could summarise the key insights as something like: “Here’s where we’re overspending and underperforming. If we clean up the targeting and refocus on Region A, we could reduce waste by 25%.”

You can keep the results of the machine learning modelling, testing and evaluation to yourself, for future work and validation. Keeping the communication simple can help build trust and connection with the stakeholders - which is crucial, especially when working on long projects.

TL;DR: EDA isn’t a checkbox. It’s the part of data science where you ask the most questions, catch the biggest mistakes, and gain the clearest insights. Ignore it, and your model may work - but not for the right reasons.