Spatiotemporal analysis of protein ligand interaction

ETL pipeline to process PDB files, analyse interaction fingerprints & visualize distributions

I recently worked with the research team under Dr. Petr Popov at Constructor University. Their team was working on protein-ligand interactions and looking for new insights that could be derived from a batch of PDB (Protein Data Bank) files. PDB files are commonly used dataformats in molecular biology. They generally store the three-dimensional structure of macromolecules to be used in analysing protein structures. This kind of work – where you use data to understand the structural and dynamic properties of molecules – is applied in many fields, from drug discovery to materials science.

I helped the team extract the molecular data from the PDB files, identify interaction-related features and analyse how these properties changed over time through various distributions.

What I used

- Python in Visual Studio for extraction and analysis

- Standard data analysis packages - pandas, numpy

- scipy.stats, statsmodels, sklearn for statistical analysis and time series tests

- MDAnalysis and ProLIF (common packages used in protein analysis and molecular biology)

- Packages & other tools for visualisation - matplotlib, seaborn, plotly, streamlit

Data source and extraction

The data provided by the research team included 501 .pdb files – each representing a frame in a molecular simulation, i.e a “snapshot”.

For extracting the data from these files, I iterated over the PDB files and for each, identified the ligand and the surrounding protein residues within a specified distance (the “box size”). This was done using MDAnalysis and ProLIF (common packages used in protein analysis and molecular biology). This selection was then converted into molecular objects to compute protein-ligand interaction fingerprints for each frame.

Some helper functions defined as follows were useful in this process:

- A function

calculate_center_of_mass(ligand_path)to compute the 3D center of mass of a ligand molecule from its structure file, which is later used to select nearby protein residues. -

get_aminoacids_dfto extract lists of interacting amino acids, and -

get_df_from_fpto convert interaction fingerprints into structured pandas DataFrames.

A main function would take the pdb file and the ligand name among other arguments to go through the other helper functions and return a dataframe with the interaction fingerprints each snapshot.

This function computes the types and strengths of interactions between the ligand and each nearby residue, storing the results in a DataFrame.

Another function process_multiple_pdb_files iterates over a list of PDB files, processes each one to get the corresponding dataframe for each file, and concatenaties them into one single dataframe.

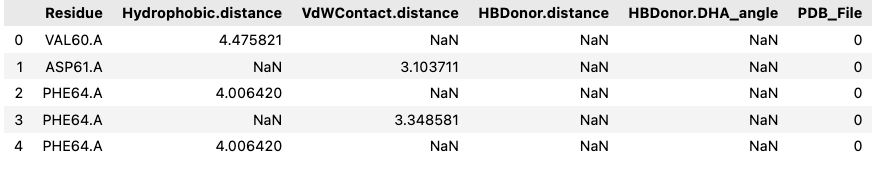

The end result of the extraction looked something like this:

Exploration

Each row in the dataframe represents a residue involved in a potential interaction with the ligand. The columns capture geometric and chemical features of these interactions. For example,

- Hydrophobic.distance, VdWContact.distance, and Cationic.distance refer to the spatial proximity between the ligand and specific residue types.

- Hydrogen bond donors and acceptors are described by both distances and angles (DHA_angle) to reflect bonding geometry.

- PiStacking features describe planar aromatic interactions using distance and angular orientation.

- Each row is also tagged with the PDB_File it came from, linking it to a specific frame in the simulation.

With the goal of exploring these metrics to see if there were any interesting patterns, I first checked for their distributions across all the frames.

A simple normalized histogram of the interaction metrics gave me the following distributions.

fig = px.histogram(

final_results_df,

x=selected_column,

nbins=50,

title=f'Distribution of {selected_column} (normalized)',

histnorm='probability density' # Normalize the histogram

)

The histnorm=’probability density’ argument shows the relative frequency of values rather than raw counts, so it’s easier to compare across metrics with different scales.

.png)

.png)

This gave me some idea of how the metrics were distributed and interestingly, pointed out that some of the metrics were Gaussian in nature while others were multi-modal.

To help the research team quickly visualize this I created a simple interactive Streamlit dashboard visualization that was shareable.

Gaussian smoothing

Based on the research team’s request, I also did a Gaussian smoothing on the distributions. This means that not only is the exact occurrences in each bin counted but the counts of each data point is spread across neighbouring bins according to a Gaussian distribution. This is what is called a kernel density estimation (KDE), where each data point contributes to multiple bins based on a Gaussian kernel.

To approximate a smoothed distribution for each interaction metric, I placed a Gaussian (normal) distribution at each data point, using a fixed standard deviation (σ) specified by a smoothing parameter. For each bin in a defined range, I computed the cumulative contribution from all Gaussians, weighted by how close each data point was to that bin center. This is so that each value can “influence” nearby bins based on a normal curve, producing a smoother alternative to a traditional histogram. (Technically it is not a true KDE but more of a binned approximation of KDE).

I was able to provide the research team with these plots as results:

.png)

.png)

Time series analysis

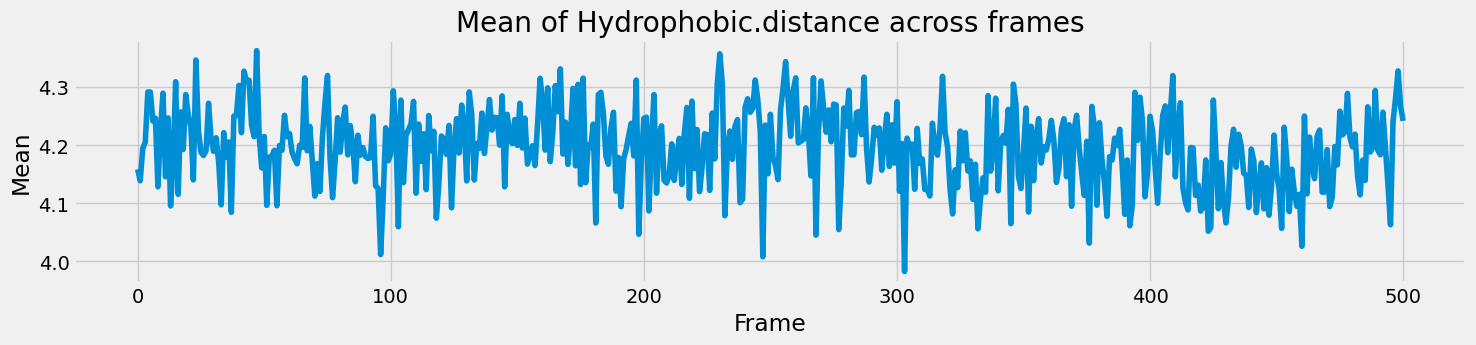

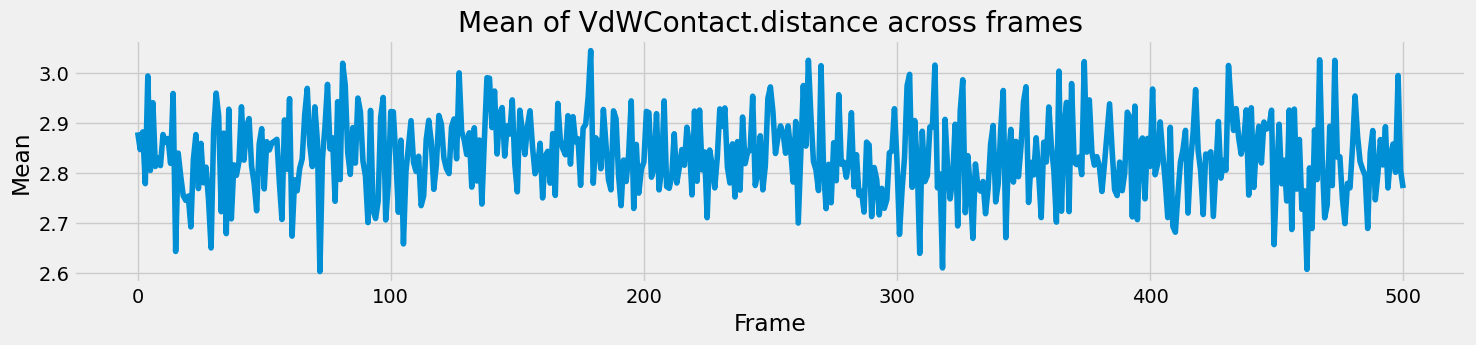

Next, I thought of checking how the different parameters changed throughout the snapshots, in a time series-like manner. However, there were multiple residues within each snapshot, with their own values for the interaction fingerprints. So it made more sense to calculate the mean value of each parameter and how that changed through the frames. A simple grouping and mean did the job here.

final_results_df.groupby('PDB_File')['Hydrophobic.distance'].mean()

The time series for all the parameters follow a similar trend - with random fluctuations around a mean and occasional spikes but there is no clear trend to observe.

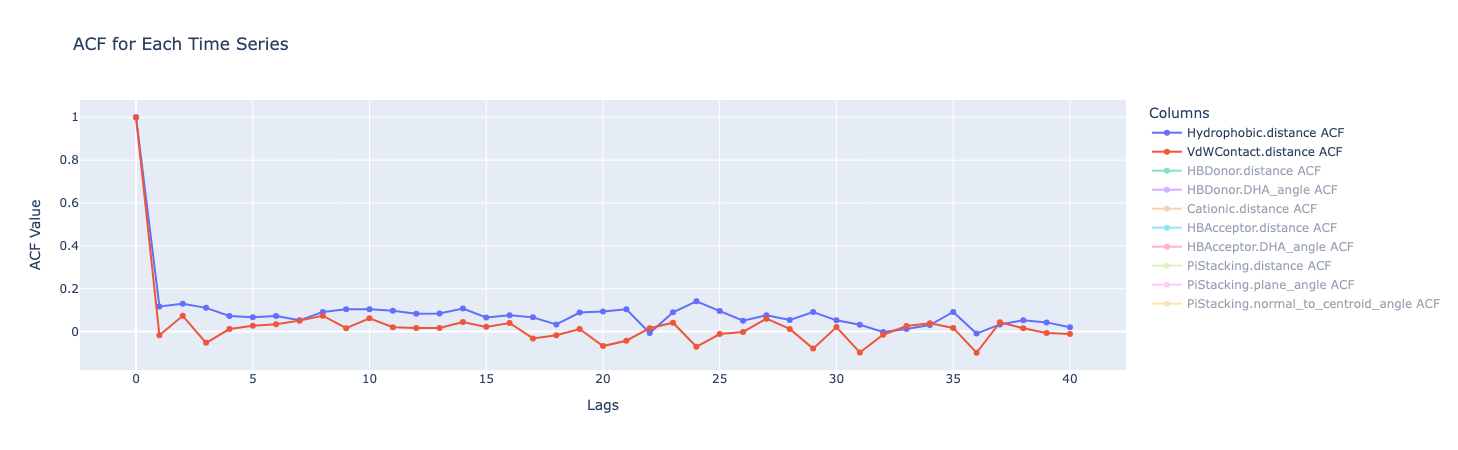

ACF, PCF and Seasonality decomposition

I thought it might also be useful to check if there were any signals that suggested that such a time series could be modelled in the future (e.g. if there was a need to predict how the various distances and metrics would change over different new frames).

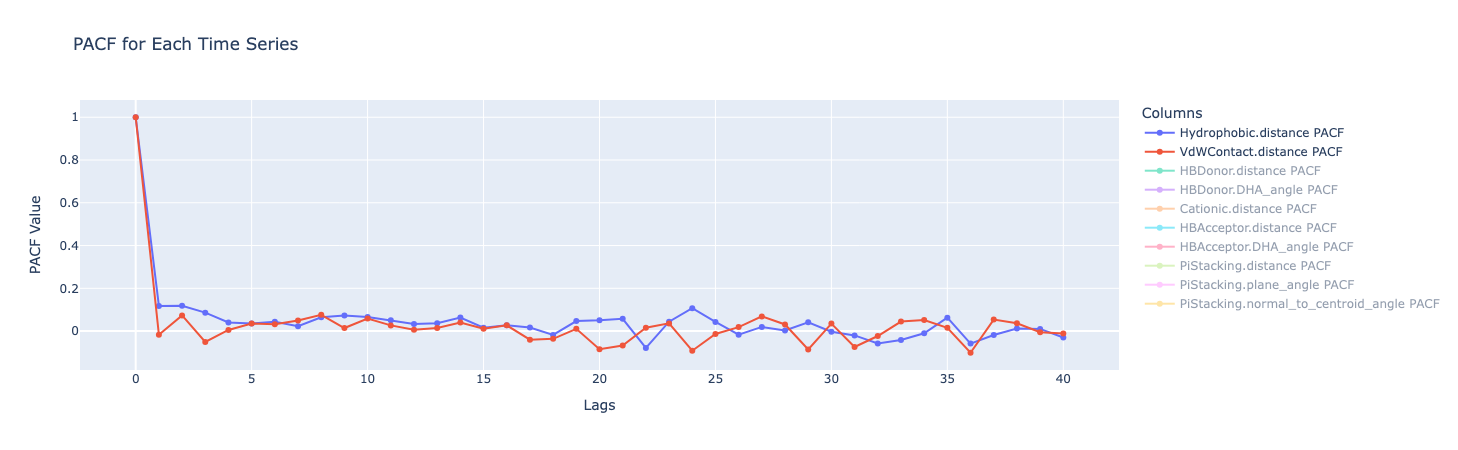

For this the commonly used ACF and PCF plots were as follows:

ACF (Autocorrelation Function) measures how much a data point is correlated with its own past values at different lags in the time series. The correlation is always 1 at Lag 0 (a value is perfectly correlated with itself). But after that, all the metrics show a sharp drop to close to 0.1, showing that any correlation quickly diminishes.

PACF (Partial Autocorrelation Function) measures the correlation between a data point and a past value in the time series, after removing the effects of the intervening data points - i.e. the direct relationship between a point and a past point, without the “middlemen.” Similar to ACF, there is a sharp drop after lag 0.

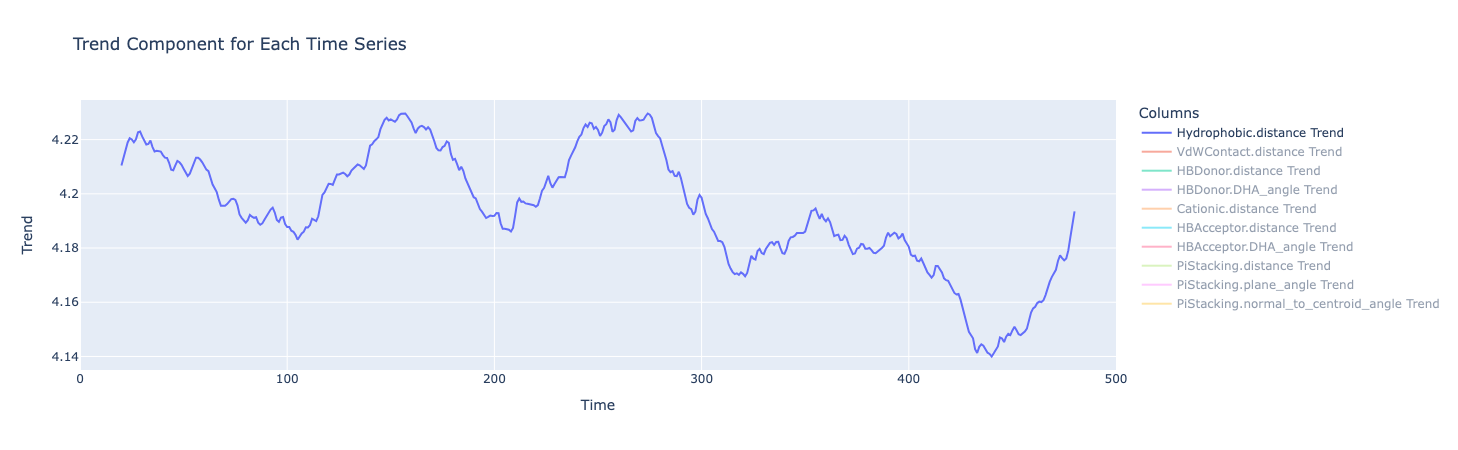

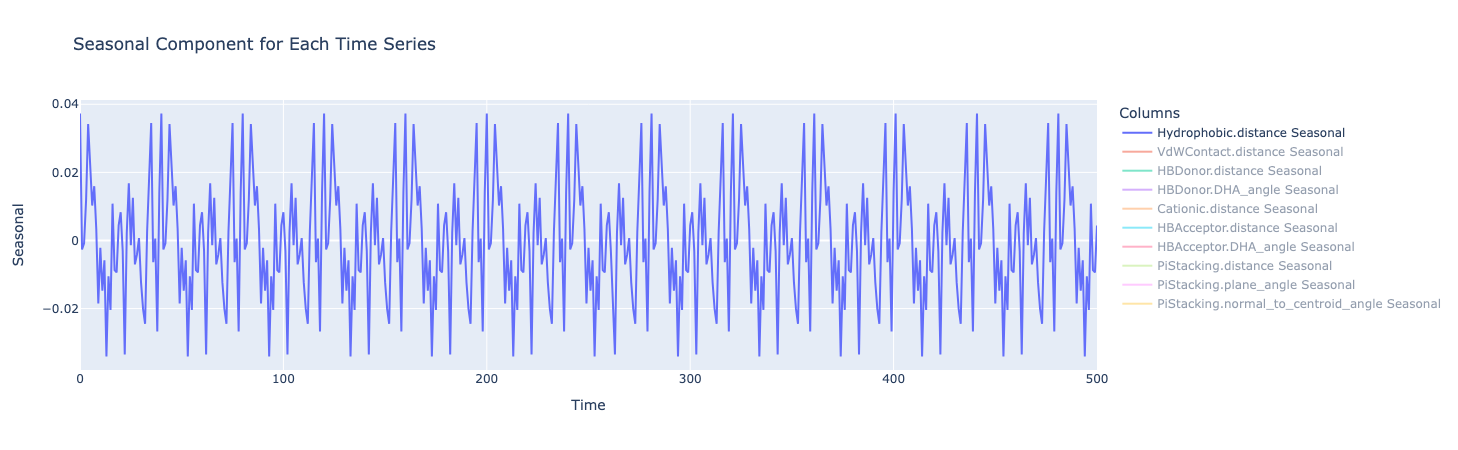

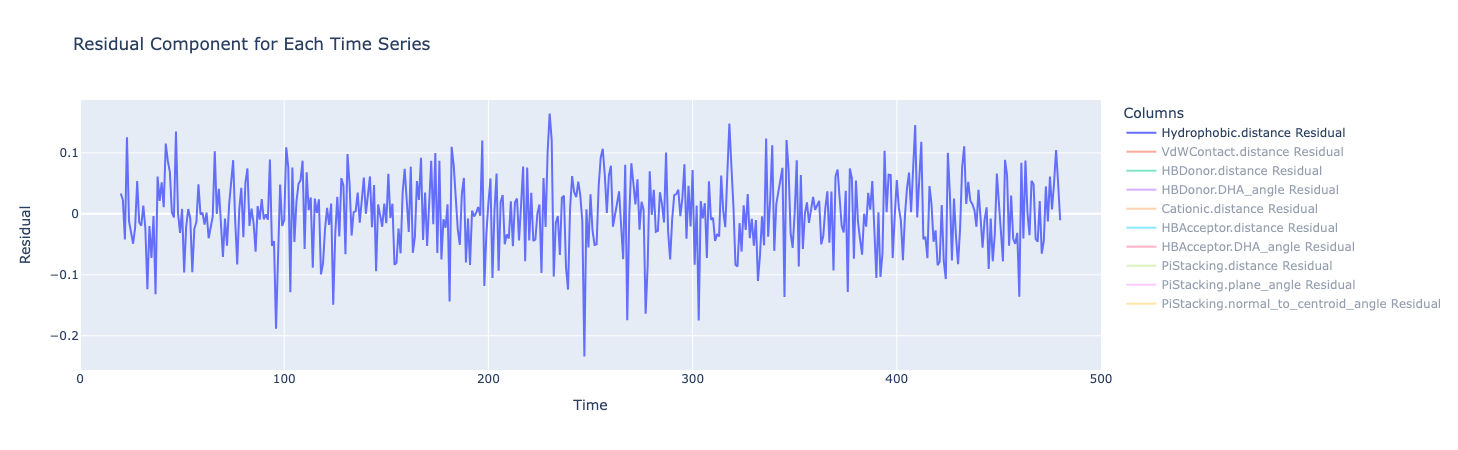

The seasonality decomposition breaks down the time series into trend, seasonal and residual components.

The trend component extract any long-term direction or pattern in the data, smoothing out the short-term ups and downs. The trend for all metrics isn’t flat, meaning there isn’t a constant average value over time. (Although there appears to be repeating peaks and valleys around every 100 or so frames, this was not seen for the other metrics, suggesting it could just be random oscillations or noise)

The seasonal component looks for any repeating patterns or cycles in the data that occur at fixed intervals. There does seem to be a regular wave-like pattern in this plot but this could also be a result of oscillations.

The residual component represents what’s left of the original data after the trend and seasonal components have been removed. Here, they fluctuate around zero, which is good and there are no obvious patterns. That means that the trend and seasonal components have successfully captured the systematic variations in the data.

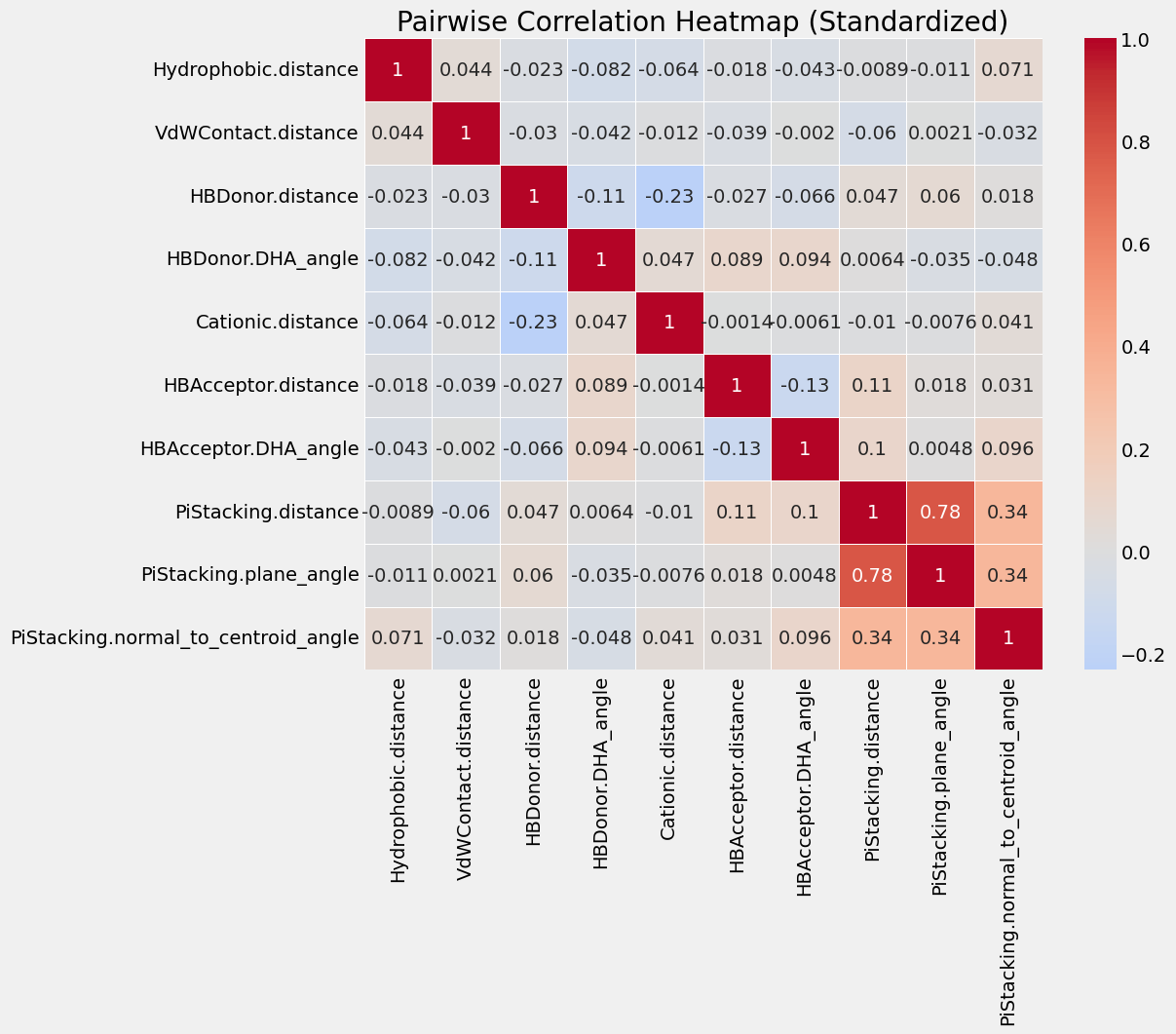

I also explored if there were any correlations between the parameters themselves in a correlation matrix (after scaling all the values using a StandardScaler).

There was no major correlations other than the distance and angle for PiStacking, which is to be expected.

Deploying into production with an ETL pipeline

The research team did find the analysis on the visualizations of the distributions to be useful though for their ongoing work. So they wanted a way of setting their own parameters to visualize - such as the folders with new PDB files, properties to visualize, the bin sizes and number of bins, the smoothing tolerance and smoothing distribution.

For this, I created an ETL pipeline that would load the PDB files from a specified folder, extract the data, transform them to calculate the distribution and produce the visualizations. This was done with the following set up

- an

extraction.pyfile with all the functions mentioned in the Data extraction step above - a

viz.pyfile with the following functions- build_smooth_distribution - that takes in as input a dataframe columns (the interaction fingerprint metrics, the scale for smoothing the Gaussian distributions, the smooth tolerance parameter and the bin parameters among others. It returns the smoothed distributions and bin centres from the input

- process_dataframes - that takes in as input the folder with the PDB files, the box_size, ligand_name and ligand_path for columns for extraction and the same arguments that build_smooth_distribution should take in, so that it can call the function. It returns the plots we need.

- a viz function - that takes in a json path where you can specify all the input arguments and calls the process_dataframes using these arguments

- main function to parse the argument from the user, namely the path to the json file which is passed to the viz function

Some challenges and lessons from this project

- The data extraction was a bit tricky. The data type (pdb files) were new to me so I had to discuss with the research team in-depth and understand the ideas of “frame”, “ligand”, “amino acids”, ”interaction fingerprints” and protein structure, what metrics needed to be extracted and how to go about doing that.

- The packages used for extraction - MDAnalysis and ProLIF - were new to me so I had to spend some time understanding the documentation and testing out object outputs.

- The extraction process itself was not straightforward (calculate center of mass of ligand, then list of interacting amino acids and then get interaction fingerprints)

- Unlike data science projects I was used to, the research team preferred using command line prompts to accept inputs - generally a path to a folder with a json file containing everything - files to extract, parameters for various functions, metrics to explore and arguments for plotting and smoothening the distributions. This took some getting used to but was manageable.

- Learning to think of the frames as snapshots and looking at them as a “time series”, and also thinking of the time series and distributions as almost interchangeable. Again, not how I have traditionally done time series projects but in this particular use case I can see how it makes sense and got used to it.

- Perhaps the most important lesson was taking the time to understand the domain, data structure and features, and discussing with the subject matter experts in-depth at the start.